You ask a large reasoning model to solve a tricky problem. It replies with neat, step by step logic. It feels like watching someone do math on a whiteboard, calm, clear, confident.

But then the doubt shows up. If that explanation is really “about the problem,” it should still make sense when another model reads it, right? If it’s just a story that fits Model A’s habits, Model B might shrug and go a different way.

In plain terms, an “explanation” here means the model’s written chain-of-thought style reasoning, the text it produces that looks like working notes. These explanations matter because people are starting to use Large reasoning models (LRMs) in science, medicine, finance, and other places where a smooth sounding answer can still be wrong. A clear explanation can help you catch mistakes, but it can also hide them.

What “explanations generalize” means for large reasoning models (LRMs)

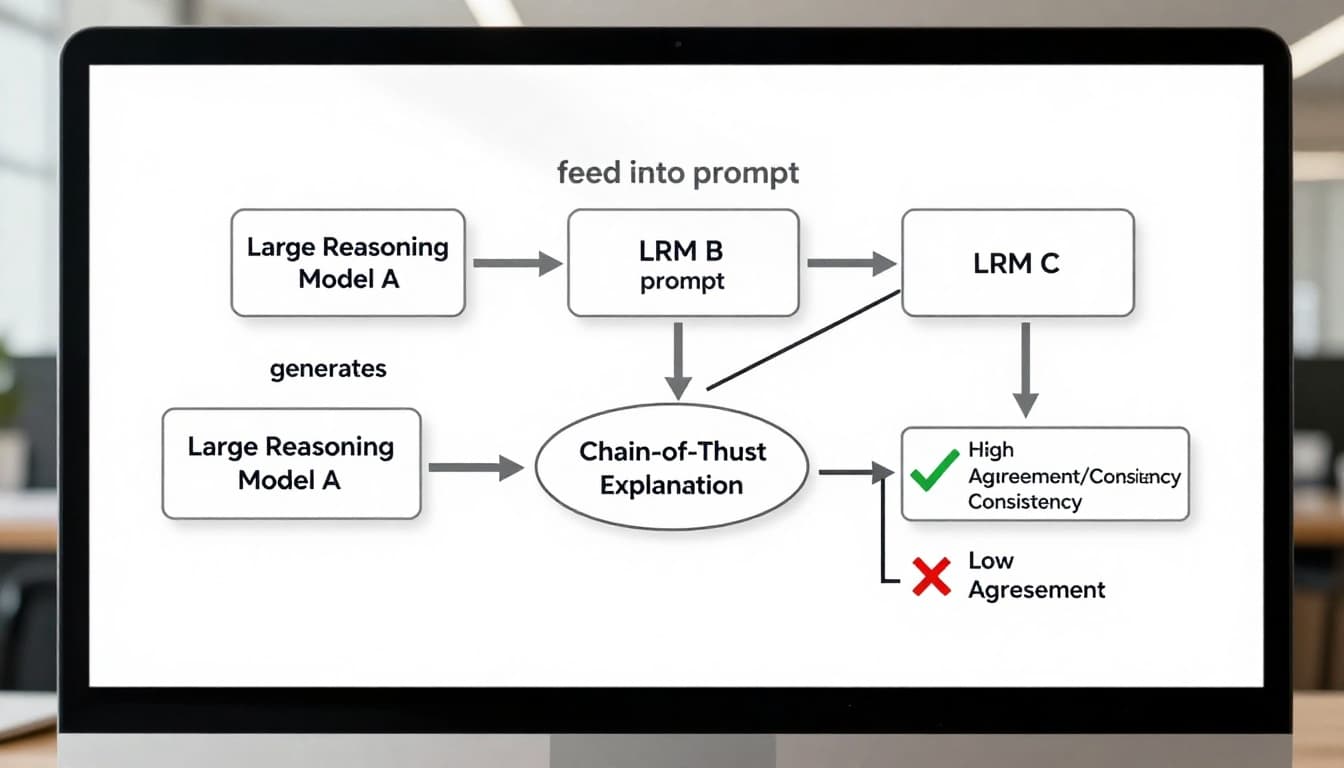

An illustration of the basic idea: one model’s explanation is reused to see if other models become more consistent, created with AI.

An illustration of the basic idea: one model’s explanation is reused to see if other models become more consistent, created with AI.

Think of an explanation like a recipe. A good recipe works in different kitchens. You might use a different oven, a different pan, maybe even different brand ingredients, but the core steps still lead you to the same dish.

That’s the vibe behind “explanations generalize.” Not “does the explanation sound nice,” but something more testable: does the explanation change what other models do?

Recent work frames this in a clean, practical way. Take an explanation generated by Model A. Paste it into the prompt for Model B (and maybe C). Then check whether B and C become more likely to answer the same way, and not just match the final answer, but follow similar decisions along the way. If they do, the explanation is acting like a reusable guide, not a one model-only artifact.

This matters in real workflows because many teams already use multiple models. One model drafts, another reviews, a third tries to break it. If explanations transfer across models, you can build a lightweight “peer review” loop without needing full access to internal weights or training data.

Chain-of-thought is not the same as the hidden reasoning

Chain-of-thought text is a readable story. The real reasoning inside the model is still a giant pattern system, basically math on vectors, not sentences. People can’t directly inspect that internal process.

So an explanation can be useful without being faithful. It might match the answer, yet still be a post-hoc narrative. This is why research on chain-of-thought faithfulness exists in the first place, because “sounds right” and “is right” don’t always line up. If you want a deeper view of this gap, see Measuring Faithfulness in Chain-of-Thought Reasoning.

In other words, chain-of-thought is evidence, not proof. It’s like a witness statement. Helpful, sometimes detailed, sometimes misleading.

A practical way to test generalization, does the explanation change other models’ answers?

The cross-model test is simple enough to do on a Friday afternoon.

- Ask Model A to solve a problem and include its reasoning.

- Copy only the explanation (or explanation plus answer).

- Tell Model B: “Here is an explanation from another model. Use it to solve the same problem. If you disagree, explain where.”

Then you measure what happens. Do B and C shift toward the same answer? Do they agree on the key steps? Do they become more consistent across multiple problems?

This checks something more important than style. It checks whether the explanation carries portable problem structure, something another model can actually use.

What current research suggests, explanations often transfer, but not always

The January 2026 result that pushed this question forward

A January 2026 paper, Do explanations generalize across large reasoning models?, takes this “recipe in different kitchens” idea and tests it directly across LRMs.

The headline takeaway, paraphrasing carefully: chain-of-thought explanations often do generalize in this behavioral sense. When one model’s explanation is given to other LRMs, those other models tend to become more consistent with each other than they would be without it. That’s a big deal because it suggests some explanations capture patterns that aren’t locked to one model’s quirks.

At the same time, the paper argues for caution. Explanation transfer is a useful signal, but it doesn’t automatically mean the explanation is correct, or that it reveals some deep truth about the world. It might just be a shared shortcut that multiple models find convincing.

Why human-preferred explanations can be more portable across models

A paper-like view representing research on explanation transfer between models, created with AI.

A paper-like view representing research on explanation transfer between models, created with AI.

One interesting pattern from the same work is that explanations that transfer well tend to line up with what humans rank as “better” explanations.

That’s not magic, it’s kind of intuitive. Explanations people like usually have:

- clearer step order

- fewer hidden leaps

- less vague wording

- small self-checks that reduce obvious errors

Those traits also make it easier for another model to follow. A different LRM doesn’t need to share the same internal path, it just needs enough structure to recreate the logic.

The paper also connects explanation transfer with reinforcement learning style post-training. In plain language, when training rewards certain behaviors (like being helpful, consistent, or aligned with user preferences), explanations may become easier for other models to reuse. Correlation is not causation, but it’s still a helpful clue about what training changes in practice.

If you’re using LRMs in research settings, this lands hard. Tools like Microsoft’s “AI scientist” style systems are built around repeated reasoning and checking, so explanation quality becomes part of the product, not decoration. Related context: Microsoft Kosmos AI Scientist capabilities explained.

A simple improvement researchers found, combine sentences to reduce disagreement

The same paper also explores a practical trick: instead of trusting one long chain as a single unit, you can treat it like a set of sentences, then ensemble at the sentence level.

The intuition is almost boring, which is why it’s good.

Long explanations often have one weak step that poisons everything after it. If you can identify shaky sentences and replace or downweight them (while keeping stronger steps), you can end up with an explanation that other models follow more consistently.

This doesn’t require fancy math for the reader to understand. It’s like editing an argument. Keep the parts that are solid. Rewrite the step that hand-waves. Then re-test across models.

It also fits a broader theme in chain-of-thought research: training and prompting often care more about structure than exact content. If you’re curious about that direction, here’s a related thread: Unveiling the Mechanisms of Explicit CoT Training.

Where explanation generalization breaks down, and how to be careful

An illustration of long-context drift, where early details get lost as the prompt grows, created with AI.

An illustration of long-context drift, where early details get lost as the prompt grows, created with AI.

Even if explanations often transfer, the failures are the part you’ll feel day to day. It’s rarely dramatic. It’s more like the model quietly taking a wrong turn because one phrase nudged it.

So here are the breakdown points that show up in real use, especially when you’re moving explanations between Large reasoning models (LRMs).

Prompt sensitivity, tiny changes can create big differences

Models can latch onto surface cues. That’s the polite way to say it. You can keep the same problem and change one sentence, and suddenly the reasoning path shifts.

A simple example: a word problem that includes extra story details (names, times, irrelevant numbers). Model A’s explanation might ignore the fluff. Model B might treat one of those numbers as important and build a whole calculation around it. Now the explanation “doesn’t generalize,” not because the idea was wrong, but because the prompt offered another plausible hook.

A habit that helps: when you paste an explanation into another model, ask it to restate the problem constraints first, in one or two lines, before it uses the explanation. This forces a quick alignment check.

Long context and niche topics, the explanation may get vague or drift

Long prompts create their own kind of gravity. The longer the input, the easier it is for a model to lose early details, mix them up, or blur them into something generic. People call it “context rot” sometimes. You feel it when the model starts repeating itself, or gives a summary that is sort of right, but not anchored.

Niche domains add another risk: models fill gaps. If an explanation includes domain terms, Model B may mimic the style without truly grounding them. The result can look consistent across models while still being wrong.

Practical habits that keep you safer:

- Keep prompts tight, trim anything the model doesn’t need.

- Ask for assumptions explicitly (“List assumptions you’re making”).

- Request a quick self-check (“Verify step 3 with a different method”).

- Test with small prompt changes, and watch for flips.

If you want a training angle on getting models to “search” more deliberately through reasoning steps, there’s relevant work like Meta Chain-of-Thought for System 2 reasoning. It’s not a cure, but it shows where the field is trying to go.

What I learned after trying cross-model explanation checks in real life

I started doing this as a habit, mostly because I got tired of being impressed by explanations that later fell apart.

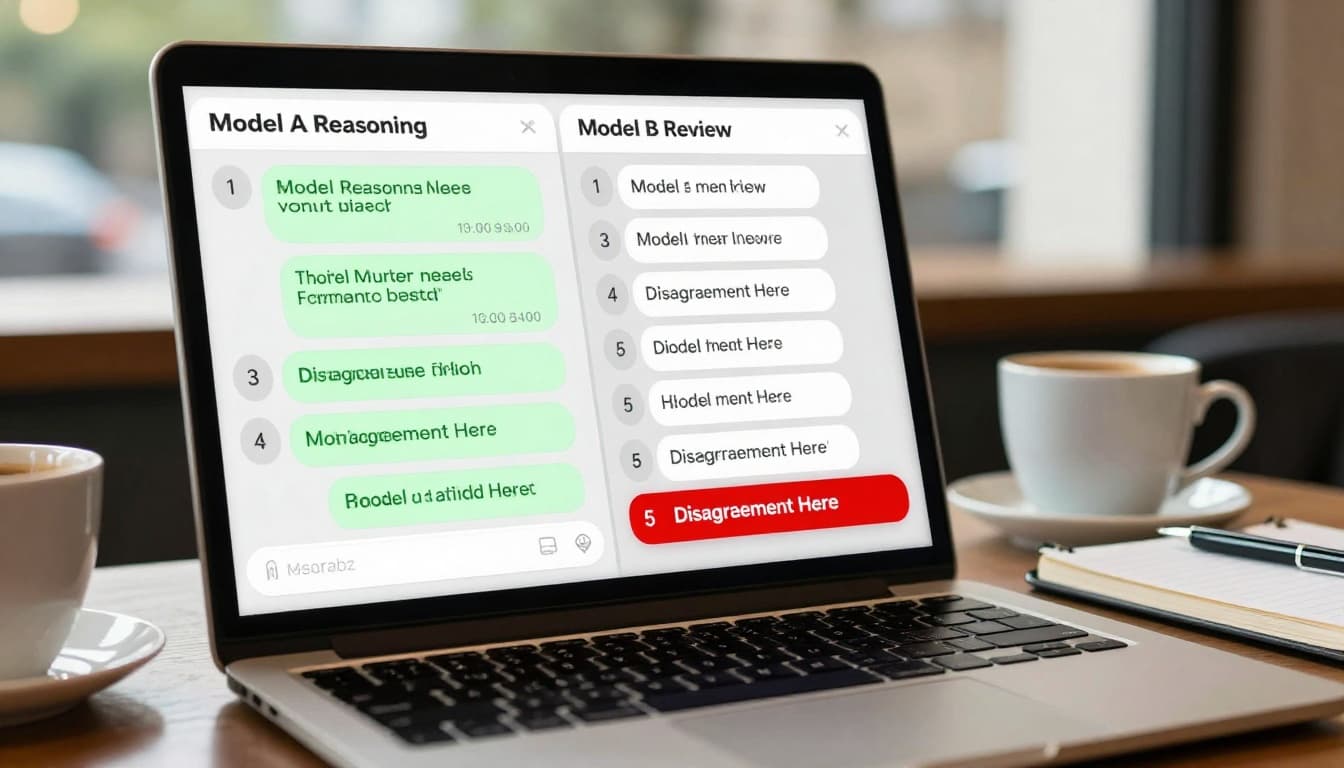

My basic routine looked like this: Model A solves a problem and shows its steps. Then I drop that explanation into Model B and tell it, “review this like you’re a picky colleague.” Sometimes I add: “If you agree, point to the step that makes it true. If you disagree, name the exact step that breaks.”

Here’s what surprised me.

First, short, plain steps transfer better than long speeches. When Model A writes five clean steps, Model B can usually follow them, or argue with one of them. When Model A writes a long chain with side commentary, Model B often drifts, and the review turns into vibes.

Second, asking for verification on one or two key steps catches real mistakes. Like, Model B might say, “Step 4 assumes X, but the prompt says not-X.” That one sentence can save you from a confident wrong answer. It’s not glamorous, but it works.

Third, agreement is a signal, not a guarantee. When both models agree, I feel better, but I don’t feel done. If it’s high stakes, I still try a small prompt change, or I ask one model to argue the opposite side. A weird number of errors only show up when you poke them.

This workflow also made me appreciate why agent systems are getting popular. When you treat models like a small team, not a single oracle, you get more chances to catch weak reasoning. If that direction interests you, this article on Manus 1.6 Max autonomous AI agent deep dive is a good companion read.

A side-by-side review setup, where one model checks another model’s reasoning and flags a disagreement, created with AI.

A side-by-side review setup, where one model checks another model’s reasoning and flags a disagreement, created with AI.

Conclusion

Explanations from Large reasoning models (LRMs) often do generalize in a practical sense. When you reuse one model’s chain-of-thought in another model’s prompt, you can often increase agreement and reduce random divergence. The January 2026 findings in arXiv:2601.11517 support that, while also reminding us not to treat explanations as ground truth.

A simple workflow is still the best: treat explanations like hypotheses, cross-check with a second model, verify the one or two steps that everything depends on, and try small prompt changes to see if the logic holds. If explanation transfer keeps improving, it could make AI “peer review” normal in science and other high stakes work, and that would be a real win, not just nice formatting.

0 Comments