“Meta changed everything” is the kind of line that spreads fast, because it feels true. The AI world moves so quickly that a single new paper, a single demo, or a single rumor can look like a clean break from the past.

But as of January 2026, the verifiable story is a little more grounded. Meta hasn’t shipped a public product that replaces chatbots overnight, and there isn’t a confirmed announcement that text-first models are “over.” What’s real is more interesting (and more useful): Meta is spending hard, publishing research, and pushing the industry toward AI that understands reality, not just sentences.

In this post, “Language-Based AI” means systems that mostly operate by generating text, token by token, then using that text to reason, plan, and respond. The big question isn’t whether text disappears. It’s whether text becomes secondary, an interface layer on top of deeper “world understanding” systems that learn from vision, time, and cause and effect.

If you build products, lead a team, invest, or just want to stay sane reading headlines, there’s a practical takeaway waiting for you.

What Meta actually did recently, and what they did not do

Timeline showing a simple view of agents now, embodied AI next, and faster acceleration after that, created with AI.

Timeline showing a simple view of agents now, embodied AI next, and faster acceleration after that, created with AI.

The loud claim floating around is that Meta has “ended” Language-Based AI. In reality, the clearest, recent Meta moves are about capacity and distribution, not a magic replacement for chat. Meta is betting big on AI across infrastructure, devices, and research directions, including open-source releases, wearables, and agent-style systems.

Based on recent public reporting, Meta has also shifted resources away from its earlier VR-heavy focus and toward AI. That includes major org changes and a renewed push to get AI into consumer hardware (like smart glasses and new input devices). In parallel, Meta is still very much in the race to train and deploy big models, including multimodal ones.

So no, there’s no verified “chatbots are dead” product moment. But yes, there’s a pattern: Meta is building the conditions for the next phase of AI, and research like JEPA-style work (world models, meaning representations) fits that direction.

Meta compute and the energy race: a giant bet on training bigger, broader models

If you want one simple explanation for why Meta looks so aggressive right now, it’s this: compute is the throttle.

Training modern AI takes staggering amounts of chips, power, cooling, and data center capacity. Meta has been signaling that it wants more of that throttle in-house, faster iteration cycles, bigger training runs, and less dependency on anyone else’s schedule.

Recent reporting says Meta is even exploring nuclear energy projects to support AI growth, with talk of unlocking multiple gigawatts of power. Whether every number holds up over time, the intent is clear: future AI is going to be energy-hungry, and Meta wants long-term supply.

Why does this matter for Language-Based AI versus “world understanding” AI? Because compute doesn’t only benefit text models. The same infrastructure supports:

- multimodal models that mix text, images, and video

- agent systems that run long workflows

- world models that learn time, motion, and physical cause and effect

Whoever can run more experiments per month usually learns faster. It’s enabling tech, not proof that text-first models are finished.

Why the “new open source model that ends chatbots” story is hard to verify right now

There are real signs of big open moves, including Meta’s public commitment to new open-source model releases. But the internet often turns “open-source models are coming” into “Meta released a new thing that kills ChatGPT,” and that last step is usually where the facts get fuzzy.

When a breakthrough is real, it leaves a paper trail you can touch. Here’s a quick checklist that helps you spot signal without getting dragged by hype:

- Model card explaining what it is and what it’s for

- Paper or technical report with method details

- Weights (or a clear reason they’re withheld)

- Benchmarks that match the claims

- Reproducible demos (not just cherry-picked clips)

- Independent testing from people who don’t work on it

For context on the research side of Meta’s “world models” push, you’ll see discussions tied to JEPA ideas and VL-JEPA-style approaches in write-ups like this breakdown of Meta’s VL-JEPA shift. It’s a real direction. It’s just not the same as “text AI is dead.”

The bigger shift: from predicting words to building “world understanding”

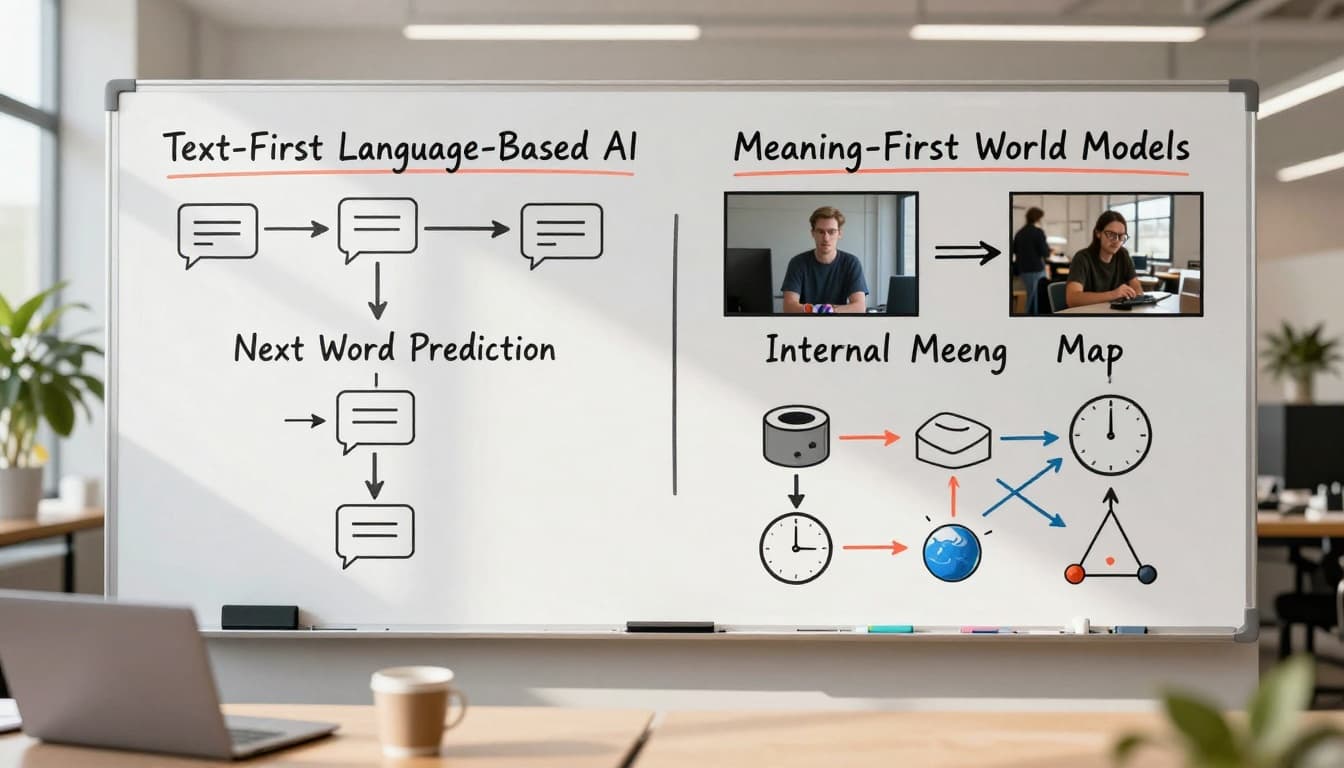

Whiteboard-style comparison of text-first models versus meaning-first world models, created with AI.

Whiteboard-style comparison of text-first models versus meaning-first world models, created with AI.

Here’s the fork in the road people are circling: do we keep scaling models that “think” by generating language, or do we move toward systems that build internal models of reality, then use language only as one output?

This isn’t just academic. It changes what AI is good at.

Language-Based AI is great when the job is basically language: summarize this, write that, explain this concept, draft a contract clause, produce code comments. It can also do planning, sometimes shockingly well, because planning can be expressed in words.

But the real world isn’t made of words. It’s made of time, objects, motion, friction, partial visibility, cause and effect. Video is full of meaning that never gets written down.

A useful gut-check: a person can “understand” a scene without narrating it. You watch a toddler grab a cup, slip, then catch it. You don’t describe frames in your head. You just… get it.

This is why “world understanding” is showing up everywhere: robotics, self-driving, warehouse automation, and even consumer devices like smart glasses. Meta’s push into wearables (including expanded Ray-Ban AI glasses production plans and other input devices) fits this trend. If AI is with you in the world, it needs to read the world.

Why Language-Based AI feels smart, and where it still hits walls

We humans have a blind spot: we equate fluent language with intelligence. It’s normal. In everyday life, people who speak clearly tend to understand more. So when an AI writes like a confident expert, our brains treat it as “smart.”

That illusion breaks in three places that keep repeating:

Time: text models don’t naturally “see” continuity. They can describe a video, but tracking what changed, what stayed the same, and what’s likely next is harder.

Physics: physical reasoning is messy. Objects get blocked, fall, bounce, break, and interact in ways that aren’t captured in text datasets.

Causality: “what caused what” is not always explicit, and next-word prediction is not a built-in causal engine.

To be fair, modern LLMs can do a lot. They plan, write code, handle multi-step tasks, and coordinate tools. For many knowledge-work problems, language-first reasoning is exactly what you want.

The more honest view is “both matter.” Language is a great interface for humans, and a strong substrate for many office tasks. World models matter when the task is grounded in reality, like navigation, manipulation, observation, or any workflow where images and time carry the key information.

If you want a wider enterprise view of where research is heading in 2026, this VentureBeat overview is a helpful snapshot.

What JEPA-style ideas change: meaning first, words second

JEPA-style thinking (Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture) is often described in a simple way: predict meaning, not words.

Instead of generating a caption for every moment, the system builds an internal representation of what’s happening, a kind of “meaning map.” It can then speak when needed, but language isn’t the core loop.

A concrete example people keep using (because it’s relatable): when you watch someone pick up a bottle, you don’t narrate every frame. You perceive the action as a whole. Meaning-first systems aim for that kind of perception.

Another key idea is temporal understanding. In some demonstrations discussed around VL-JEPA-style work, the model’s “belief” stabilizes as it sees more evidence, like a guess that becomes more confident once the full action plays out. That’s much closer to how humans process events. We revise as we see more, then we lock in.

If you’ve been following the conversation around Yann LeCun’s view that next-word prediction isn’t the same as intelligence, reporting like this piece on his post-Meta direction shows how strongly that camp is pushing for world models.

So is this really the end of Language-Based AI, or the start of hybrid AI?

The most likely outcome isn’t “language dies.” It’s that language stops being the whole machine.

Hybrid AI is a cleaner mental model:

- Language as the interface (instructions, collaboration, explanations, negotiation)

- World models as the core for perception and prediction (vision, time, object permanence, causality)

- Agents as the action layer (tool use, workflows, software control, eventually robotics)

That combination fits what the market is buying. Teams don’t just want better text. They want systems that take a goal and complete the work, then show receipts.

This is also why headlines about “the end” miss the point. The shift is more like the early smartphone era. The first versions were flawed, but the direction was obvious. Same thing here.

(If you want a practical look at agents moving from demo to real autonomy, this internal piece on Manus 1.6 Max and end-to-end AI agents is a good reference point.)

2025 to 2027: agents now, embodied AI next, then faster feedback loops

A timeline that’s been making the rounds, and honestly matches what many builders are seeing, goes like this:

2025: autonomous agents start handling real workflows. They still “think” mostly in language, but they can execute tasks, use tools, and coordinate steps without constant babysitting.

2026: embodied AI becomes more visible at scale. Robots and physical systems get better world models, better perception, and better control loops. This is where warehouses, factories, and logistics can change fast.

2027: the bigger question becomes acceleration. If systems get better at improving themselves (through faster training cycles, automated research loops, and stronger feedback), the pace can jump. That’s not a prediction set in stone. It’s a planning risk.

If you want more context on why 2026 is shaping up differently, this internal guide on what AI in 2026 looks like connects the dots across agents, devices, and physical systems.

What changes for safety when models “think” in hidden meaning space

Safety gets weird here, and not in a fun way.

With Language-Based AI, you can sometimes audit intent by reading outputs. It’s imperfect, but at least the system “speaks” its reasoning, even if that reasoning is partly theater.

Meaning-first systems can be more opaque. If a model reasons in an internal latent space, you may not get a clean chain-of-thought in text. That can mean higher capability with less visibility.

Practical safety moves start looking like this:

- stronger evaluations for video understanding and long-horizon action, not just text benchmarks

- monitoring actions and tool calls, not only what the model says

- sandboxing agent behavior, tighter permissions, and clear human override

- testing in simulation before real-world deployment (especially robotics)

This isn’t fear talk. It’s just the cost of building systems that act, not just talk.

What this means for you, whether you build AI or just use it

The best way to read “Meta changed everything” is: Meta is placing bets that line up with where AI is already going. Not only chat, not only bigger text models, but systems that can observe, remember, and act in the real world.

If you’re leading a team, it’s a good time to stop judging AI progress only by how good the writing sounds. Start watching how well systems handle time, images, and outcomes.

If you’re curious about the broader “AI scientist” and agent direction, this internal breakdown of Microsoft’s Kosmos and autonomous discovery workflows shows the same pattern: less chat for chat’s sake, more systems that run the work.

If you are building products: go beyond chat, design for action and reality

Here’s a simple rule that keeps teams from wasting months: if the task depends on the real world, don’t design it as a text-only problem.

Start with the workflow. Where does the information come from, what changes over time, what needs to be verified?

Then build up from there: add tools, add memory, add vision when it helps, and measure success by the outcome, not by how polished the explanation sounds. A support agent that writes pretty replies but doesn’t actually resolve issues is still a failure.

You don’t need a humanoid robot to think this way. Even software agents working inside a browser have “world” signals, screenshots, page state, timing, and feedback.

(Planned image for this section in a full publish: a realistic warehouse robot scene to represent embodied AI and automation.)

What I learned watching this shift up close (a personal take before we wrap)

I’ve caught myself overtrusting confident text more times than I want to admit. It happens when the output is smooth, the tone is steady, and it “sounds like” someone who knows. Then you check one detail and it’s off. Not always, but enough that you learn a new habit: verify the parts that matter.

What I’m watching now is simpler than it sounds: does the system understand time and cause and effect, or does it just talk well?

That’s why JEPA-style ideas grabbed my attention. Even when early versions are imperfect (and they are), the direction is a signal. It reminds me of the first iPhone vibe: missing features, rough edges, still obviously pointing somewhere real.

Language-Based AI isn’t going away. I still use it constantly. But the future doesn’t feel like “better chatting.” It feels like models that can see, track, predict, then act, with language as the wrapper.

(Planned image for this section in a full publish: an AI-generated collage showing a chat window beside camera and robot sensor imagery to represent hybrid systems.)

Conclusion

Meta hasn’t released a verified public system that ends Language-Based AI as of January 2026. But the industry is clearly shifting toward multimodal and meaning-driven systems that handle time, vision, and real-world feedback, especially as agents and embodied AI ramp up.

The practical move is simple: treat big claims like a prompt, not a fact. Look for papers, model cards, benchmarks, and independent tests, then build skills around agents plus world understanding.

The next wave won’t just talk better. It’ll notice more, and it’ll do more.

0 Comments