AlphaFold was the moment a lot of us realized AI could do real science, not just write text or spot cats in photos. It took a long-standing biology problem, protein folding, and made it feel… solvable.

Now Google DeepMind is taking a bigger swing with AlphaGenome. Proteins are one thing. DNA is the whole instruction manual, plus all the sticky notes, bookmarks, and crossed-out lines that decide what gets read in the first place.

Here’s the twist: AlphaGenome isn’t trying to “read” DNA like a string of letters. It’s trying to predict what those letters do inside cells, which genes turn on, which stay silent, how RNA gets stitched, how DNA opens and closes, and how far-apart regions can still influence each other. And that matters because most human genetic differences sit outside genes, in the messy regulatory part where we usually shrug and say, “we’re not sure.”

DNA doesn’t sit in a straight line, it folds and loops inside the nucleus (created with AI).

DNA doesn’t sit in a straight line, it folds and loops inside the nucleus (created with AI).

What AlphaGenome actually does when you give it a stretch of DNA

Think of AlphaGenome like a “biology simulator” that starts from raw DNA sequence and outputs predictions that normally take many separate lab tests.

You feed it a stretch of DNA, and it predicts signals that biologists measure with experiments like RNA-seq (gene activity), ATAC-seq (how open the DNA is), ChIP-seq (protein binding and chemical marks on chromatin), plus 3D contact maps from Hi-C style assays (which DNA regions physically touch). If you want the official overview and access details, DeepMind’s post on AlphaGenome and genome understanding lays out what the model is meant to do and how they’re releasing it.

What makes it feel different is the scale. AlphaGenome can look at up to about 1 million DNA letters at a time (a megabase), while still making predictions down to individual base positions. Most older genomics models had to choose: big context with blurry detail, or sharp detail with tiny context. This one tries to keep both.

And it’s not “one model for one job.” It’s one model instead of many, trained to predict lots of functional signals together, so it can reuse shared patterns biology keeps repeating.

From one input to thousands of biological readouts, in one pass

DeepMind describes AlphaGenome’s outputs as thousands of “genome tracks.” A track is basically one layer on a map. Same location, different overlays: gene expression, accessibility, binding, histone marks, and so on.

In the human version alone, AlphaGenome predicts 5,930 tracks across many tissues and cell types. The mouse version adds 1,128 more. That’s wild because it means a single DNA sequence can be scored across thousands of biological “views” without building separate models each time.

This unified setup matters for a simple reason: biology isn’t modular. Splicing affects expression, DNA accessibility affects binding, binding affects chromatin marks, and they all feed into each other. Training them together can help the model learn deeper rules, not just memorized patterns.

Why long-range DNA context matters (your genes have far-away switches)

If genes were light bulbs, non-coding DNA contains a lot of the switches. Some switches are close, many are far. Enhancers can sit tens of thousands of letters away and still change a gene’s activity.

That’s why the megabase window is a big deal. DeepMind reports that shortening the context at inference time hurts performance. In plain terms, the model needs the surrounding “neighborhood” to make good calls.

It also matches real biology. DNA folds in 3D, so two far-apart regions in the sequence can become neighbors in the nucleus. AlphaGenome tries to predict pieces of that spatial wiring too, not perfectly, but enough to help connect distant regulatory elements to the genes they control.

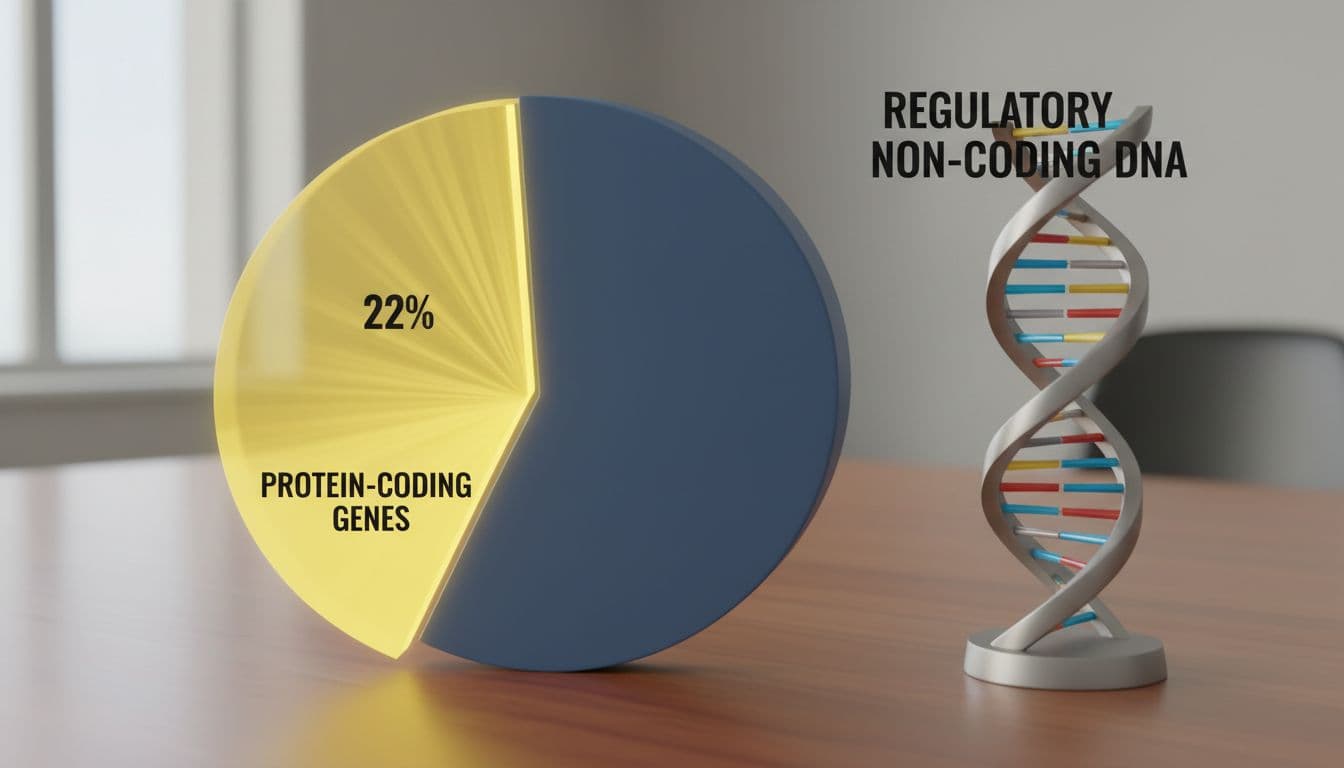

Why this could change medicine, especially for the 98 percent of DNA that does not code for proteins

Most people learn DNA as “genes make proteins.” That’s true, but it’s also incomplete. The majority of disease-linked variation often shows up outside protein-coding regions, inside regulatory DNA where interpretation is harder.

That’s why AlphaGenome’s focus on non-coding function hits so hard. If a variant doesn’t change a protein sequence, you still want to know: does it change a transcription factor binding site, does it open chromatin, does it disrupt splicing, does it push a gene up or down in one tissue but not another?

For a good non-technical framing of this “dark matter” problem, Scientific American’s write-up on DNA’s hard-to-interpret regions captures why researchers have been stuck for so long.

Most DNA isn’t protein-coding, but it still controls what cells do (created with AI).

Most DNA isn’t protein-coding, but it still controls what cells do (created with AI).

Variant effects in plain English, what happens if one letter changes

AlphaGenome can score a mutation by asking, “If I change this one letter, what shifts downstream?” That includes predicted changes in gene expression, splicing signals, chromatin accessibility, protein binding, and chromatin marks.

Speed is part of the story too. DeepMind reports that on a high-end GPU, one variant can be evaluated in under a second. That doesn’t sound dramatic until you remember researchers often need to scan millions of variants across cohorts.

They also tested AlphaGenome across a wide set of benchmarks (dozens of variant-effect tasks). The takeaway they emphasize is that the distilled version of the model matched or beat strong existing methods in almost all tests. If you want the peer-reviewed detail, the Nature paper is here: regulatory variant effect prediction with AlphaGenome.

Better clues for gene expression, splicing, and disease-linked variants

Two terms show up a lot in this space:

An eQTL is a variant linked to changes in gene expression. A GWAS is a study that connects variants to diseases or traits across big populations.

On eQTLs, AlphaGenome improved the correlation between predicted and observed effect sizes from 0.39 to 0.49 in a finemapped dataset, and at a high-accuracy threshold it recovered more than twice as many known eQTLs as a comparison model. That’s not magic, but it is meaningfully better at telling which way the volume knob turns.

On GWAS interpretation, DeepMind reports AlphaGenome could assign a confident direction of effect to at least one variant in nearly half of over 18,000 credible sets, and the sets it helps resolve often don’t overlap much with classic statistical approaches. That’s interesting because it hints the model is adding new biological hypotheses, not just echoing the usual signals.

Also Read: Macrohard: Elon Musk’s Plan to Replace Microsoft with AI, What You Need to Know

How Google built AlphaGenome at this scale, and what it still struggles with

There’s a very “Google” engineering story underneath the biology. AlphaGenome was built in JAX and trained on TPUs, with parallelization tricks to handle giant sequences without blowing up memory.

Under the hood, it uses a hybrid approach: part of the model focuses on local sequence patterns (the tiny motifs proteins recognize), and part focuses on long-range relationships (how distant regions work together). It also learns multi-scale representations, including 1D sequence-style features and 2D contact-map style features.

Still, it’s not perfect. DeepMind calls out limits that matter in practice: very distant effects are harder, tissue-specific predictions aren’t flawless, and training data is still biased toward better-studied, often protein-coding, parts of the genome.

The trick, local DNA words plus long-distance context

The easiest analogy I’ve heard is “words and chapters.”

Local motifs are like words. They’re short, specific, and they matter for things like transcription factor binding and splice sites. Long-range regulation is like chapters. You can’t understand a plot twist without reading what came earlier.

AlphaGenome tries to read both at once. That’s also why base-level resolution matters. Splicing errors can happen because of a change at a single base. Accessibility can hinge on tiny edits too. The model’s big context helps, but it still needs sharp vision.

Distillation and multimodal learning, why one smaller model can beat many big ones

DeepMind trained multiple heavy “teacher” models first, then distilled them into a single faster “student” model. During distillation, they also introduced synthetic mutations, so the student gets practice seeing how small edits ripple through predictions.

The other big ingredient is multimodal training. Instead of learning gene expression alone, or splicing alone, AlphaGenome learns them together. DeepMind reports this combined training tends to outperform single-task training, especially for mutation-effect prediction, where signals are connected in messy ways.

What I learned digging into AlphaGenome, and how I would use it if I were a researcher

Reading through the details, my main “oh… wow” moment was realizing how much of genetics is still blocked by the non-coding part. We’ve had the letters for years. The hard part is turning letters into likely consequences. That’s where most variant interpretation still slows down, and yeah, it can feel like walking in fog.

If I had access to AlphaGenome in a real research workflow, I wouldn’t treat it like an oracle. I’d treat it like a fast hypothesis machine.

I’d start with one suspicious variant from a patient cohort or a GWAS region. Then I’d check three things: does it change predicted binding (a switch), does it change predicted accessibility (is the switch reachable), and does it change predicted expression or splicing (does anything downstream move). When those signals line up across tissues, it gives you a clearer story to test in the lab.

That’s the part that feels new to me. Instead of chasing one narrow readout at a time, you can see a stacked set of clues, all from the same DNA input, and you can move faster without guessing as much.

A simple way to imagine the workflow: variant in, predicted biological shifts out (created with AI).

A simple way to imagine the workflow: variant in, predicted biological shifts out (created with AI).

Conclusion

AlphaGenome looks like a foundation model for regulatory genomics, the kind that can turn “unknown variant” into a shortlist of testable biological effects. It won’t replace experiments, and it won’t solve every tissue-specific mystery, but it can make the first pass sharper and a lot faster.

If you want to track how this evolves, it’s worth skimming broader coverage like the BBC’s report on AlphaGenome, then comparing it to the technical release notes from DeepMind. The real story over the next year is simple: how often do these predictions hold up in wet-lab follow-ups?

If you’re watching this space too, keep an eye on the API and community releases, and tell me what you’d test first with AlphaGenome.

0 Comments